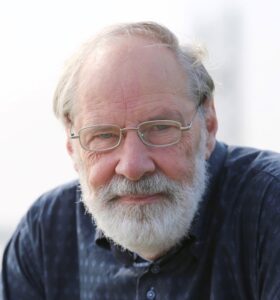

Dr. E.P. Sanders werd op 13 juli jl. door de Council of Centers on Jewish-Christian Relations (CCJR) voor zijn hele oeuvre onderscheiden met de Shevet Achim Award 2016. Dr. Sanders is beroemd geworden vanwege zijn baanbrekende werk als exegeet van het Nieuwe Testament en kenner van de zgn. intertestamentaire periode.

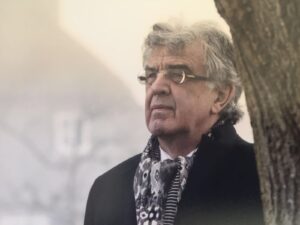

door Dick Pruiksma

Sanders stond met zijn boek “Paul and Palestinian Judaism” aan het begin van wat later “the New Perspective on Paul” zou gaan heten. Als één van de eersten nam hij de moeite om de brieven van de apostel voor de volkeren te lezen in een adequater kader van de geloofsovertuigingen en de geloofspraktijken van het Jodendom van Paulus’ tijd. Hij muntte daarbij de term “covenantal nomism”, waarmee gezegd wil zijn dat het Jodendom, ook in de dagen van Jezus en Paulus, niet een religie is die als doel heeft de mensen door het doen van goede werken (de werken der wet) rechtvaardig voor God te maken. Integendeel, de Torah is bedoeld om mensen in een verbondsgemeenschap met God te hóuden.

In Philadelphia zetten dr. Sanders zijn opvattingen nogmaals uiteen onder de titel “Paul and Christian theological anti-Judaism”. De organisatie had twee respondenten uitgenodigd. Prof. Adele Reinhartz, een leerling van Sanders, hoogleraar aan de Universiteit van Ottawa. En ook ondergetekende had de eer prof. Sanders toe te spreken. Hij noemde zijn bijdrage: Deconstructing the Dichotomy.

In Pruiksma’s reactie op Sanders’ werk worden drie vragen beantwoord die door de conferentieleiding hem werden voorgelegd:

a. Vertel over de betekenis van Sanders’ werk tegen de achtergrond van jouw kerk en werk.

b. Hoe heeft zich Sanders’ invloed daar ontwikkeld?

c. Wat zijn jouw ideeën over de integratie van Sanders werk in de projecten van de ICCJ?

De complete tekst van de bijdrage is als volgt:

Deconstructing the dichotomy

A response to Prof. E.P. Sanders

Annual Conference ICCJ, Philadelphia. July 13, 2016

Rev. Dick Pruiksma

Dear Professor Sanders,

ladies and gentlemen,

June 4, 1987 was a remarkable, if not historic day in my life. On that Thursday namely, almost thirty years ago, I bought my first book written by Professor E. P. Sanders: “Jesus and Judaism”. I brought my copy. I paid no less than 61 guilders and 50 cents in that pre-Euro era. Moreover, I must have been very impressed by Professor Sanders’ work: I bought two books that very day. I also became the proud owner of “Paul, the Law and the Jewish People”. Which upped the price of my purchase to a whopping 96 guilders and 35 cents. I can assure you, ladies and gentlemen, these books have been more than worth every cent they cost. Let me not forget to mention some other books: “The historical figure of Jesus” – in Dutch translation: Jezus, mythe en werkelijkheid – and most certainly “Paul and Palestinian Judaism”.

Why did I buy these books? Well, simply because for me a new world was opened; a really new perspective on Paul, and not only on Paul. Dear Professor Sanders, you may not have been aware of it every day, yet it is true that you have been accompanying and guiding me on my theological ways for almost thirty years now. Me, a Dutch Protestant pastor, serving his congregations. And when I offer you, ladies and gentlemen, a few reflections this afternoon, I would like to start with outlining a little bit of my background as a Protestant pastor in the Netherlands to explain why the work of Professor Sanders has been so important in that theological environment.

As a second step in my reflections, I would like to say something about how his theological innovation developed in my church and in the area of Jewish-Christian dialogue. Or not.

And last but not least, a third step. Being a former General Secretary of this organization, I would like to share with you a few thoughts about how we could integrate the perspectives prof. Sanders and others introduced us to in our international dialogue work. And all this in great gratitude to Professor Sanders and many others for what they taught us. They paved the way.

Obviously it was not sheer coincidence that I bought those books written by prof. Sanders that 4th of June 1987. The purchase was not entirely without history, completely from the blue sky. I am of course part of a tradition. And I am proud of the many and early attempts that were made in Protestant circles in the Netherlands in order to reduce the theological gap between Jews and Christians by making a radical end to the teaching of contempt. The most important tool obviously was the effort to read the Scriptures over and over again and to re-think Jewish-Christian relations. But this time this work was not done without but with our Jewish friends and colleagues. Even before the Second World War, voices were heard in the Netherlands addressing the huge gap between Jews and Christians as not according to Scriptures as Scripture was then newly understood in the framework of renewed or just starting Jewish-Christian dialogue. The aim, even in those early days, was to bridge the gap that had existed for centuries, confirming the superiority of Christianity over Judaism. As prof. Sanders this afternoon said: Many Christians think that Judaism in Paul’s days was a terrible religion and that its adherents were miserable.

A turning point -though unfortunately not much noticed when published- has been the thesis of Dr. J.J. Meuzelaar, published in 1961 entitled “Der Leib des Messias”, in which he explores the metaphor of the body of Christ, the “sooma tou Christou” in Paul’s letters. Meuzelaar published his thesis in German as he hoped to influence the in 1961 not yet published volumes of the Theologische Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament. His thesis is remarkable and as it is written in German it is accessible also for the few people who do not speak Dutch.

Meuzelaar’s professor Van Unnik already had said in 1947 that “no serious study of earliest Christianity is possible without knowledge of Judaism, its language, its history and way of thinking.” i)

This view certainly was not commonplace in 1947. In the introduction to the 1979 photographic reprint of Meuzelaar’s thesis, we read that Meuzelaar himself

It’s amazing to see so many years later now, 2016, that both quotes span a period as early as from 1947 to 1961. And it is even more amazing that we, studying theology ten or even fifteen years later at the seminary of my church in the provincial town of Kampen, we were taught nothing about all this. But we bought books you know. And we rebelled against our professors, inviting representatives of the “Tenach and Gospel” group founded already in 1957 from Amsterdam. iii) We organized our own series of lectures to emphasize and explain the necessity that we are aware, while reading, studying and preaching the New Testament: that the vast majority of these writings originated in and only can be understood within the context of the multicolored, first-century Judaism.

What motivated us students? I think it was a strong intuition that the theological dichotomy , iv) to quote Magnus Zetterholm, between Judaism and Christianity, which is so deeply anchored in our theological genes and which fine tunes all our terminology and hermeneutics, that this theological dichotomy is not based on historical facts but on a way of reading Scripture that is determined by normative theology. And that, consequently, these theologically normative convictions also define “the other”, our partner in dialogue. So, the work of Professor Sanders fell on fertile ground, to quote the parable. For here we studied books on Jesus and Judaism, on Paul and Palestinian Judaism, in which the gospels and letters were not placed in a black-and-white scheme against their Jewish background, but in which the New Testament writings were considered very much part of the Jewish world of the first century CE itself.

These observations caused a New Perspective on Paul. Magnus Zetterholm, in his introductory essay to the volume “Paul with Judaism” summarizes the importance of Prof. Sanders’ work as follows:

So far so good. Let us take a second step. How did all this develop where I live? Unfortunately, I can be brief on that as far as my own setting is concerned. Because it did not develop that much at all. And regrettably this is mainly due to the distance between academia and ecclesia. Of course, scholars like Peter Tomson with his “Paul and the Jewish Law” and others from Holland and Belgium absolutely contributed to the continuing theological process. Peter Tomson for instance focusses on the role of Halacha in Paul’s letters and is convinced that the first letter to the Corinthians is much more important than the letter to the Romans.

But within the churches and its departments for Jewish-Christian dialogue the focus was for many years mainly if not only on the Middle East, burdening the dialogue and hindering the theological process. So many of us, pastors and priests, busy in our congregations and parishes, missed out on a lot of important issues.

For instance, the developments from the New Perspective on Paul to a radical new perspective on Paul, now preferably called “Paul within Judaism.” If it is correct that Judaism is NOT about work righteousness but can be characterized as covenantal nomism, and when indeed Paul found nothing wrong with the Torah, prof. Sanders explained it this afternoon, then why would Paul have left Judaism?

I come back to the previous quote from Meuzelaar’s “Der Leib des Messias”: “The theme of the letters is not determined by the later contrasts between synagogue and church, but by those between Jews and Greeks, or Israel and the nations.” vi) In my own words: it is not the opposition, the contrast, the contradiction between covenantal nomism and justification by faith/salvation by Christ, but between Jew and Greek or Israel and the nations, that is fundamental to Paul. Living as a Jew, Paul does not distinguish three categories on our way to salvation. It is not about Jews and pagans as the basis dialectical contrast ánd Christians as the synthesis. It is all about Jews and non-Jews. We need to re-invent our vocabulary.

Anders Runesson rightfully points out the dangers that hide in our use of words we think are absolutely clear.

Step by step, Christian scholars, here in the United States more closely cooperating with their Jewish colleagues than in Europe and elsewhere, they are deconstructing the theological dichotomy of Judaism and Christianity in the first century.

And on the Jewish side? In an article called “Where Do We Go from Here? Unresolved issues and Suggested Solutions” Rabbi Gary Bretton-Grantor writes:

When I come in a third step to a brief conclusion of these reflections, I can easily follow Rabbi Gary’s thoughts. It is indeed of utmost importance that the theological expertise present in ICCJ is used to strengthen this process of deconstructing the theological dichotomy or Judaism and Christianity.

The ICCJ is the platform par excellence where Jewish and Christian scholars (can) come together in an international context not only to summarize what has been discovered so far but even more to make this scholarly debate accessible to grass root interfaith workers in our member organizations.

The paradigm shift in the past decades is amazing. After Jesus has come home “Die Heimholung Jesu” it is now time for Paul and others to follow him. What we now call Christianity started as a specific form of Judaism. Mark Nanos and Anders Runesson suggested to name that specific form of Judaism “Apostolic Judaism.” And the so-called parting of the ways, well, we know how long that took.

My concluding plea therefore is to bring the scholarly expertise together, from this side of the pond and from other parts of the globe, Jews and Christians, academia and ekklesia in a new theological project. We do not call that project of course “Paul within Judaism”. That is the specific Christian way of speaking. But bringing Judaism and Christianity, let us say: what has become later Rabbinic Judaism and non-Jewish Christianity, bringing those together to the point they were not two separated let alone hostile entities, but part of one though multicolored Jewish world, this process of deconstructing the theological dichotomy can really move forward Jewish-Christian relationships today.

We could enter into a deep theological, hermeneutical dialogue. Let’s do it.

Notes:

i Quotation by K.H. Kroon in his introduction to the 1979 photographic reprint of J.J. Meuzelaar, “Der Leib des Messias”, Kampen, 1979, V.

ii Ib.

iii The institution still exists. See http://leerhuisamsterdam.eu/, date of consultation: july 2016

iv See M. Zetterholm, “Paul within Judaism: the State of the Questions”, in Mark D. Nanos and Magnus Zetterholm (eds.), Paul within Judaism, Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle, Minneapolis: Publisher 2015,33

v Zetterholm, ib., 43.

vi J.J. Meuzelaar, “Der Leib des Messias”, Kampen, 1979, V.

vii A. Runesson, “The Question of terminology”, in Mark D. Nanos and Magnus Zetterholm (eds.), Paul within Judaism, Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle, Minneapolis: Publisher 2015, 59

viii Rabbi Gary Bretton-Granatoor, Where Do We Go From Here? Unresolved issues and Suggested Solutions, http://archive.adl.org/main_interfaith/nostra_aetate1bd4.html#.V3ZxubiLSLI, date of consultation: july 2016